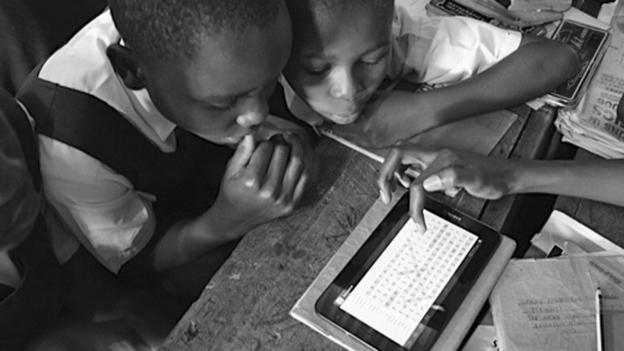

(Copyright: eLimu)

There has been a surge in technology initiatives aimed at delivering

education in the developing world. But is there too much focus on flashy

devices?

In a tiny classroom tucked inside one of Nairobi’s sprawling slums, the 34 class eight students of Amaf primary school wait anxiously for the 4 o’clock bell.

At this time, twice a week, headmaster Peter Lalo Outa instructs students to put away their textbooks, assembles them into groups, and pulls out seven sleek tablet computers for the after-school lesson. One day, the students watch a video explaining the process of composting manure. On another, they’ll watch the animals they study come to life through videos, pictures, and interactive games.

“Our curriculum in Kenya is like a punishment to children, they feel they have to do it because it’s compulsory,” explains Outa. “With these tablets, our students really enjoy learning.”

Amaf school is one of two institutions piloting software by eLimu, a Kenyan education-technology startup that develops apps and content for small, touch-screen, wifi-enabled Android-powered tablets.

“We’re using the tablet as a tool through which information, ideas and passions can grow,” says eLimu founder Nivi Mukherjee,

eLimu works with local teachers, partners and developers to design localised, digital content meant to push primary education beyond the typical “chalk and talk” approach common in many classrooms. The start-up wants to show that digital content can be cheaper, better, and more effective at getting kids to learn.

“Our books have a limit,” says Outa, “but these tablets go beyond - with videos, photos and more practical learning.”

In Kenya, education is still one of the country’s biggest development hurdles. Although primary school was made free in 2003, resulting in nearly 100% enrollment, today less than one third of primary school pupils possess basic literacy and math skills for their level, according to Uwezo, a four-year initiative researching the state of education in east Africa. On any given day, 13 out of 100 teachers are absent from school, it says.

“Overcrowding in classes, inadequate teachers, and lack of learning and teaching materials” are all enormous challenges to education, admits John Temba of Kenya’s Ministry of Education.

Splash and flop

eLimu may be the latest attempt to harness technology for education, but it’s certainly not the first. For decades, organisations have been using technology to broaden universal access to information and make learning more interactive.

For example, in the 60’s, educational radio programs were used to reach students in Australia’s remote outback. In the 70’s, some Latin American countries were using radio to standardise and broadcast lessons to rural areas. And in the 90’s and 2000’s, there was an enormous push for computer labs in classrooms and internet connectivity.

These days, the spectrum of e-learning is much wider, and the goals more ambitious.

For example, there is the $100 laptop project - a rugged, solar-powered, “children’s laptop” with an open source learning platform developed by MIT’s One Laptop Per Child (OLPC). Since 2006, founder Nicholas Negroponte has traveled the globe lobbying countries from Uruguay to Rwanda to commit to buying “one laptop per child” to improve education worldwide.

Then there is India’s Aakash Tablet, India’s “answer to MIT’s $100 computer,” according to Kapil Sibal, India’s minister of communications and information technology. The $50 tablet - to be built in India with Google’s free Android software - was unveiled in 2010 by two Indian tech entrepreneurs.

And there is a host of others, including programmes from tech firms like Microsoft and Intel, to a project that distributes e-readers (like Kindles) to kids in the developing world.

You are Welcome.

ReplyDelete