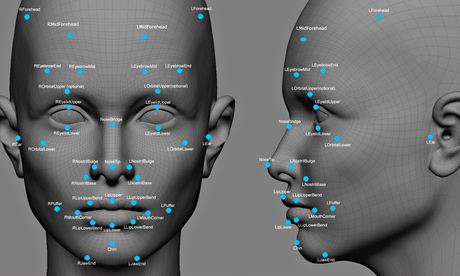

Facial recognition data points: 'While facial recognition algorithms may be neutral themselves, the databases they are tied to are anything but.'

This summer, Facebook will present a paper at a computer vision conference revealing how it has created a tool almost as accurate as the human brain when it comes to saying whether two photographs show the same person – regardless of changes in lighting and camera angles. A human being will get the answer correct 97.53% of the time; Facebook's new technology scores an impressive 97.25%. "We closely approach human performance," says Yaniv Taigman, a member of its AI team.

Since the ability to recognise faces has long been a benchmark for artificial intelligence, developments such as Facebook's "DeepFace" technology (yes, that's what it called it) raise big questions about the power of today's facial recognition tools and what these mean for the future.

Facebook is not the only tech company interested in facial recognition. A patent published by Apple in March shows how the Cupertino company has investigated the possibility of using facial recognition as a security measure for unlocking its devices – identifying yourself to your iPhone could one day be as easy as snapping a quick selfie.

Google has also invested heavily in the field. Much of Google's interest in facial recognition revolves around the possibilities offered by image search, with the search leviathan hoping to find more intelligent ways to sort through the billions of photos that exist online. Since Google, like Facebook wants to understand its users, it makes perfect sense that the idea of piecing together your life history through public images would be of interest, although users who uploaded images without realising they could be mined in this manner might be less impressed when they end up with social media profiles they never asked for.

Google's deepest dive into facial recognition is its Google Glass headsets. Thanks to the camera built into each device, the headsets would seem to be tailormade for recognising the people around you. That's exactly what third-party developers thought as well, since almost as soon as the technology was announced, apps such as NameTagbegan springing up. NameTag's idea was simple: that whenever you start a new conversation with a stranger, your Google Glass headset takes a photo of them and then uses this to check the person's online profile. Whether they share your interest in Werner Herzog films, or happen to be a convicted sex offender, nothing will escape your gaze. "With NameTag, your photo shares you," the app's site reads. "Don't be a stranger."

While tools such as NameTag appeared to be the kind of "killer app" that might make Google Glass, in the end Google agreed not to distribute facial recognition apps on the platform, although some have suggested that is no more than a "symbolic" ban that will erode over time. That is to say, Google may prevent users from installing facial recognition apps per se on Glass but it could well be possible to upload images to sites, such as Facebook, that feature facial recognition. Moreover, there is nothing to prevent a rival headset allowing facial recognition apps – and would Google be able to stop itself from following suit?

Part II coming soon...

Part II coming soon...

No comments:

Post a Comment